Three ways to keep Europe’s retail investors investing

An unprecedented boom in retail investing is sweeping Europe, powered by the growth of zero-commission brokers. While a hugely promising trend, it’s important to keep smaller investors engaged by ensuring they get good outcomes. This means better execution, sufficient access to competitive, multilateral exchange-traded products and greater financial education. In this way, retail investors can keep contributing to building an equity culture consistent with the goals of the Capital Markets Union.

The number of zero-commission brokers active across Europe has surged in the past three to five years, driven by neo/online brokers. One consequence of this rise has been an unprecedented golden age for retail investing. In France for instance, where neo-brokers have made significant inroads, retail investors executed twice as many transactions in March 2020 compared with the previous month, a trend that shows few signs of flagging.

Since the start of the pandemic however, zero-commission brokers have received considerable grief for, among other things, contributing to the ‘gamification’ of investing. We feel this criticism is misguided. For many retail investors drawn to day-trading, this style of investing tends to be a conscious choice. And by lowering barriers of entry to markets, especially for young people and small savers, these new players have made valuable progress toward building an equity culture in Europe in line with the goals of the Capital Markets Union.

But we are concerned that current regulation increasingly threatens to deliver bad outcomes for small investors that could drive them away from markets. Among the most harmful features of the current landscape in our view are payment for order flow models (and their inherent conflicts of interest), inadequate investor education and easy access to complex structured products. In order to help improve outcomes for smaller investors, Europe’s regulators should make targeted changes to the rules governing the brokerage sector.

Here are three suggestions for doing so.

Boost Competition for Retail Orders

A specific model of payment for order flow (PFOF) prevalent in the United States has received an outsized amount of attention lately. Under this model, the wholesaler arms of liquidity providers route flow to their own internal execution platforms. Critics say this practice results in a situation where no genuine open competition for retail order flow exists. This is said to lead to a worse outcome for retail investors than if multiple liquidity providers had competed for execution.

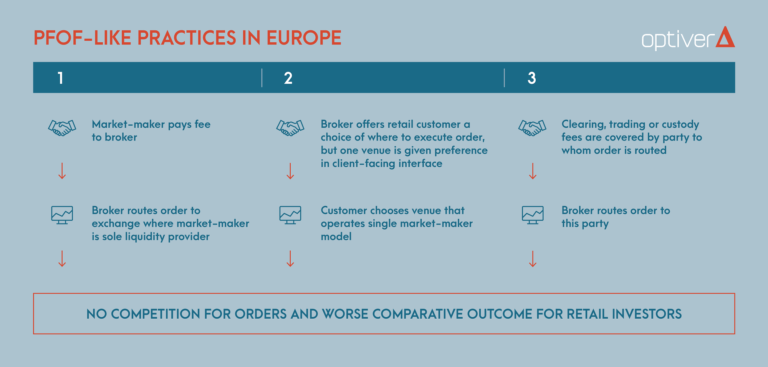

Little attention however has been paid to market practices that result in equally uncompetitive outcomes that are common among brokers in the EU. While these practices differ from the PFOF practiced in the U.S., they carry the potential for similar conflicts of interest. Addressing these PFOF-like arrangements is key in our view to ensuring better outcomes for small investors.

For instance, we have observed practices where retail brokers route their orders to execution venues that operate single market maker models, meaning there is only one designated liquidity provider for individual product classes. In many cases, the liquidity provider pays a fee to the broker in exchange for routing its client orders to the particular exchange where the market maker is the sole liquidity provider (see graphic).

We have also observed market practices where brokers offer their customers a choice of execution venue, but in their marketing or client-facing interface, preference is given to one particular venue, which typically operates a single market maker model. Moreover, we are aware of a market practice where clearing, trading or custody fees are covered by a party when routing trading flow to them. This is in effect a cost discount that incentivizes brokers to send their client orders to specific institutions for execution.

The fact that brokers route their orders to execution venues where there is no genuine competition from multiple liquidity providers raises questions. For instance, are these brokers delivering on their best execution obligations to their clients? And even if they are, do clients get the level of price improvement that genuine competition for that order flow between multiple liquidity providers would deliver? Exacerbating these issues is an uneven playing field across Europe, with PFOF-like models widespread in some member states but absent in others.

We support in theory the European Commission’s recent proposal to ban payment for order flow across the EU. However in its current form the proposal focuses on the PFOF practiced in the U.S., and therefore does little to address practices such as the ones described above. Broader language that would capture the models widespread in Europe is needed for the regulation to have its desired effect.

Encourage Exchange-Traded Products

Among the range of offerings provided by brokerages to European clients are structured products such as CFDs, turbos, warrants and sprinters that in our view lack the transparency, liquidity and accurate pricing to make them appropriate for retail investors. Compared with their counterparts in the U.S. and Asia, non-professional investors in Europe also have relatively limited access to competitive, multilateral exchange-traded products like listed options, futures and ETFs.

This results in a situation where most retail investments flow into structured products rather than into more transparent, less costly and more liquid exchange-listed products. We would also point out that regulatory regimes are inconsistent across member states. We have doubts over whether this situation truly serves retail investors or the long-term interests of market participants as a whole. To remedy this, we offer up two suggestions.

First, regulators should designate a new category of “semi-professional investor” in MiFID 2. This class of investors should be subject to more stringent suitability, knowledge and loss absorption capacity tests than the most inexperienced investors category. As such, they should be allowed to invest in both structured products as well as exchange-traded products.

This also means limiting investors in the most inexperienced category – retail – to trading solely in competitive, multilateral exchange-traded products. We feel this is justified because structured products carry larger inherent risks – including counterparty credit risk – than comparable exchange-traded products that can deliver the desired exposure to the same underlying.

Second, regulators should scrap the requirement in MiFID 2 that mandates that key investor information documents (KIIDs) be made available in local languages. KIIDs describe risks, costs and potential returns, and must be distributed to investors when they buy investment products. While in theory local-language KIIDs could aid understanding, in practice we feel that English is widely spoken and understood throughout the EU, making such a requirement superfluous. It’s also proven to be a cost barrier for issuers considering launching ETFs across the single market. Scrapping it would incentivize issuers to offer more ETFs in Europe, a net benefit for investors.

Better Financial Education

We feel the current regulatory framework around investor education falls short. While progress has been made in providing investors with relevant information in an easily digestible and accessible manner, there are still holes. For instance, the current suitability/knowledge test required for opening an investment account does not sufficiently inform investors about the risks of leverage and trading on margin. The industry as a whole should place more focus on educating investors about basic financial concepts, the value of investing and the functioning of capital markets. We have been encouraged by recent educational efforts from the likes of the London Stock Exchange and Euronext.

Conclusion

We are not convinced by arguments that zero-commission brokers represent a threat to investors. These new players have helped Europe make significant progress toward the goals of the Capital Markets Union. What should be of concern however are the uncompetitive market structures, uneven playing fields, complex structured products offerings and insufficient investor education that are features of the brokerage sector as a whole. Targeted reforms that help improve the experience for smaller investors would allow the EU to capitalize on the hugely promising trend of greater retail involvement in its capital markets.

Further Reading

- The European Commission’s strategy for retail investors.

- A study by the French Financial Markets Authority on retail investor activity during the pandemic.

- A Reuters article about “meme-stock mania” in Europe.

- A Financial Times story about the elusiveness of ETFs for retail investors.

Optiver supports open discussion and debate on all market structure topics that would lead to an improvement of the market.

To discuss this paper – or any other market structure topic – reach out to the Optiver Corporate Strategy team at [email protected]

DISCLAIMER: Optiver V.O.F. or “Optiver” is a market maker licensed by the Dutch authority for the financial markets to conduct the investment activity of dealing on own account. This communication and all information contained herein does not constitute investment advice, investment research, financial analysis, or constitute any activity other than dealing on own account.